Roots

How do we value our natural environment? How do we value the experience of that natural environment, and consequently, the artist’s response to natural, ecological, environmental experiences or predicaments? These questions are at the root of a complex web of discourse around how we view, value, manage, preserve and call attention to the places where we live. Mrinal Mandal, once a traditional landscape artist, is motivated by a sense of urgency concerning local and global environmental crises, in particular in his native Jhargram in West Bengal to move towards ecological art. He is looking to express, connect and communicate strategies for dealing with environmental issues by combining his artistic practice with collaborative, installation-based projects. The resulting artwork he hopes to produce will be a multi-media and interdisciplinary work connecting art, technology, geology, geography, and other disciplines.

Jhargram, once a sylvan idyll, has been manipulated, destroyed, polluted, and transformed by socio-political factors. Mandal recognizes the need to fold nature and environmental issues into art-making by understanding the individual’s place in nature, the history and consequences of human interaction with nature, and the natural materials themselves. Throughout human history, nature has been manipulated. The environment was a cog in the wheel, a material to be used. Traditional landscape painters urged their viewers to see a spiritual presence in all of nature. Mandal feels to continue is this vein is impossible. Are we still searching for that spiritual centre in its most pure and untainted state though? The contradictory and intended tragedy of landscape painters is that as they celebrated and displayed the beauty, simplicity, and spirituality of the wilderness they encountered, their attention to this beauty whetted the appetite of a culture on the move. They are only partly responsible for a long parade of culture wanting to possess that environment. Plenty of other trajectories in the industrial evolution made this parade possible. The parade into the wild has a long history and has links to other human phenomena such as population explosions, radical industrialization, and human negligence, ignorance, and material greed. The parade has ultimately led us to a critical situation where the ultimate survival of life on the planet has been compromised.

Nature and the environment have long inspired contemplation and reflection in Mandal as an individual and as an artist. He thrills in the discovery and celebrates the beauty of the wilderness, the amazing potential in nature to rebound from damage and the diversity of materials that exist in nature. He is very much a visual reporter – although much more than merely that – taking details and views, as well as commentary on a fast vanishing landscape. He refuses to take the judgmental route, though, finding fault in progress and condemning the future. His aim is not be an environmental activist, calling attention to many negative issues. His aim is to have an impact on his environment through his art, improving, managing, and maintaining what he has grown up with. His proposed multi-disciplinary installation project aims to focus on effecting change – going beyond the simple observation or appreciation of nature and characterize the emerging ecological paradigm as a shift from the parts to the whole; from structure to process; and from objective to contextual knowledge.

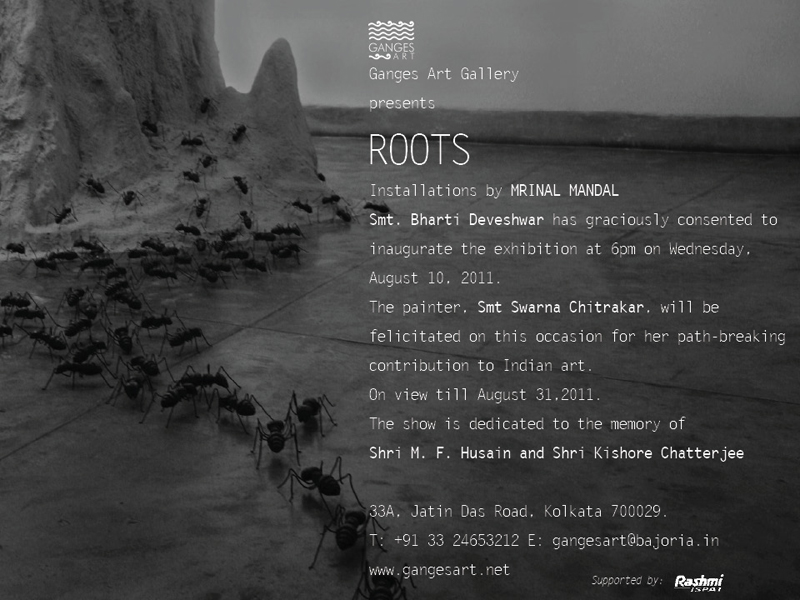

A recurring theme in his current work is the notion of connectivity: the concept that each bit of the ecosystem plays a part in a complicated puzzle of life on earth. He links the predicament of nature to the future of humankind by arguing that resources have limits and it is essential to our survival both as individuals and as a planet. He feels we need to become better listeners and partners with our environments. Ecology is a natural centre for this dialogue of connectivity.

Over the last forty years, many artists have responded to the land and to their environments through projects such as earthworks, land art, and reclamation projects, addressing issues such as urban sprawl, mining, deforestation, pollution and waste. Goals for these works ranged from exploring the use of natural materials in art, challenging the notion of the gallery or museum space by using landscapes as sculpture, raising awareness about industrial environmental casualties, confronting viewers with issues that are normally hidden. The variety of goals continues in Mandal’s art but he also wishes to heal, manage, maintain, reconfigure and reconstruct specific ecologies. He intends to weave together Jhargram’s rich history and his conceptions, responses and visions as a contemporary artist to the land and its future. It is his intention that materials will be interwoven with the work, letting the land speak for itself.

The challenge is to give value to environmentally and ecologically sensitive art by folding it into the mainstream of contemporary art. The problem is that even within the art world, environmentally sensitive work is not given its due weight, both aesthetically and otherwise. There are, thus, three distinct aspects to Mandal’s practice: the physical, the social, and the spiritual. The intended collaboration is with the environment or the physical site itself. The social discipline ties together natural systems with human social systems, and the spiritual ties nature to mythology, the sacred, and belief systems. A project of this nature goes to show that a work of art can be functional, extremely well-informed, scientifically correct, and still be aesthetically appealing. Like contemporary cultural theorists, artists have to slip some of the bonds of history, and think carefully about how to define interdisciplinary practice and what it means to act upon these ideas in the world as Mandal does. Widening the circle of resources can both inform the artist’s work, and also make connections allowing the work to operate in other communities such as the social, scientific, philosophical, and historical realms. In this interdisciplinary model, artists expand their practice by moving out side their discipline and its institutionalized relationship to society.

Mandal’s art is a bold and informed attempt at giving value to both the environment and to environmental art and point for a shift in his artistic and social thought. He poses challenging questions about changing paradigms and aims to explode the humanist notion of the autonomous individual as the solitary centre of all meaning, and replacing it with a sense of human dependence on a stable climate, fertile soil, living rivers and forests as well as a sustainable biosphere. Jhragram may not return to the Eden it once was, but this project aims to give us a glimpse of what can be. It shows a respect for the origins of our environmental landscapes, a belief in the value of current ecologies, and a conviction for solving crises through dialogue.